Classic Review: High Plains Drifter (1973)

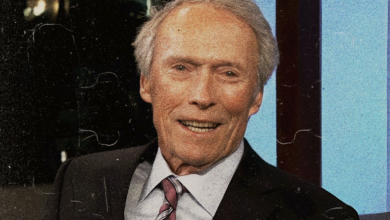

At this point Clint Eastwood is as well recognized for his achievements as a director as he is for his work as an actor. He has been fully accepted by film critics as an auteur who brings his own distinctive stylistic touches to every film that he makes and no-one would think to question his bona fides as a scholar of the Western genre. Audiences have grown accustomed to digesting Eastwood pictures on a meta level, as he appears to be preoccupied with interrogating his own macho persona. His current reputation ensures that modern audiences struggle to understand how significant his early directorial works were in advancing his career prospects. Moviegoers weren’t prepared to see The Man with No Name struggle with girl problems and obsessive stalkers but Play Misty for Me exposed them to a rarely explored facet of Eastwood’s persona. His early directorial efforts feel like works produced by an artist who is desperate to gain artistic freedom and that provides them with an urgency that cannot be found in The 15:17 to Paris.

High Plains Drifter was the first Western he ever helmed and he wears the influence of his former collaborators rather heavily. He draws on Sergio Leone’s taste for picaresque storytelling and Don Siegel’s unfussy camera movements, whilst incorporating reverent homages to both filmmakers into the climactic gunfight. The resulting mélange of filmmaking styles that would seem to stand in opposition to one another is not entirely cohesive. As a director, Eastwood still seems resistant to the idea of taking big swings and chooses to hedge his bets at times when the screenplay calls out for stylistic excess.

The highly allegorical narrative of High Plains Drifter centers around Lago, an isolated mining town in the American Old West. The inhabitants of the settlement are presented as cowards who rely on hired gunmen to protect them from bandits. They are shocked and horrified when the enigmatic Stranger (Eastwood) rides into town and takes out all of the members of their security crew. In an effort to appease the Stranger, the townsfolk offer him the opportunity to become a dictator of sorts. He quickly takes control of the town and begins to humiliate individuals who dare to question his authority. Under his direction, the men of Lago become skillful fighters who are capable of murdering their enemies, but leaders within the community continue to stand in opposition to his plans.

Many of the film’s thematic preoccupations will be familiar to those who have seen Akira Kurosawa’s highly influential samurai epics but High Plains Drifter is primarily distinguished by its vivid, exuberant use of color. The plains referenced in the film’s title are represented as one big hallucinatory mirage and Eastwood makes the most of the extreme contrast between the wide blue skies and the sparkling waters that surround the town. The visuals become even more operatic when the Stranger instructs the townsfolk to paint the town red and starts to refer to Lago as hell on earth. By the time the climax rolls around, fire and brimstone imagery take center stage and the film fully commits to literalizing the visual metaphor at its center.

Ernest Tidyman’s pedestrian screenplay rarely displays the lightness of touch or sleight of hand that elevates Leone’s spaghetti Westerns. This means that the eye-popping cinematography is relied upon to spice up scenes that proceed along fairly predictable lines. However, Tidyman did make the crucial decision to stretch out the film’s opening act for an unusually long period of time. The opening showdown is staged in a conventional manner, which only makes it all the more disorienting when the next forty minutes are devoted to an anthropological study of the political tug of war that occurs after the usual status quo is thrown into disarray.

High Plains Drifter commercially successful hit paved the way for future Eastwood epics and stands out among his filmography for its surprisingly bold deployment of bright colors and rough textures. In many ways, the film feels like one in a long line of self-reflexive Westerns that meditate on the history of the genre. That isn’t necessarily a bad thing, as it does gain a certain emotional resonance when considered within the context of Eastwood’s career.