Why I’m dancing as Bill Cosby

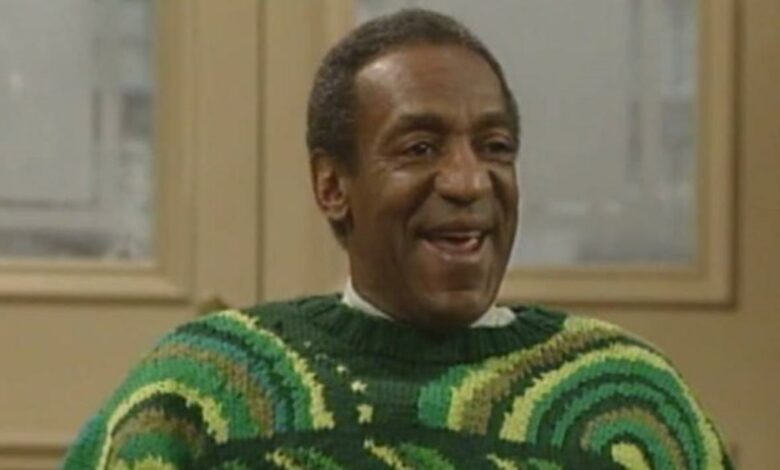

Last winter, I had the blues,” American performance artist Season Butler tells me over a drink. “The kind of blues that make you take to your bed for a TV binge. I was looking for something comforting and non-threatening – so I started binge-watching The Cosby Show, from season one, episode one. It was the wrong choice.”

It certainly was. Ever since the first allegations of ѕехսаւ assault were made against Bill Cosby in the early 2000s, it has been hard, if not impossible, to watch The Cosby Show in the same way many of us did as children.

Now, Butler is addressing the social architecture that can allow a powerful man in the public eye to allegedly ѕехսаււy assault a large number of women without facing prosecution or even public vilification – by dancing.

For her latest project, Happiness Forgets, Butler will singlehandedly reenact the opening dances from all eight seasons of The Cosby Show. Remember the top hats and twirls? The slow-shoe shuffles and swing-out steps? In between each dance, she will riff on her personal and creative experiences of race, gender, ѕех and class.

“Bill was in my blind spot,” says Butler. “I was like a lot of people – it was in the back of my head, but I was thinking of it more as a he-said-she-said thing. I thought it was a grey area.” So she started reading up on the story, to find out why certain characters disappeared from the series.

“Unlike Rolf Harris or Jimmy Savile or even Woody Allen, the race issue complicated it for me,” says Butler. “There was a feeling of betrayal. This taints one of the seminal moments in black culture.” Butler didn’t grow up wanting Cosby to be her father – her own father was a comedian and actor who was involved in the US civil rights movement.

But she liked the show, and she liked the fact that a sitcom about a middle-class black family existed. “In a funny way, it seems so apolitical,” she says. “It’s this gentle world. Which is, politically, what makes it so problematic – this need to come across as white and bourgeois.”

Butler has confronted problematic subjects before. While her writing is largely concerned with issues of intersectionality – how race, age, gender, ability status and ѕехսаւıty intertwine – she has also performed work where she gutted, plucked, and cut the feet off a chicken, before serving it up to an audience. She’s performed under a piano at the BFI in London and written about falling in love with a stranger on a bus. But this project is her most contentious, as it tackles the terrifying triptych of ѕех, power and race. “It doesn’t have an ending or a resolution,” warns Butler. “The only character in the performance is me, but I’m not trying to speak for all women, or all black people, or everyone who grew up in the 80s and 90s.”

Although Happiness Forgets involves dancing, Butler is not, she insists, a dancer. “I just had an instinct that to remake these dance sequences would be the thing,” she says. “There’s something about the black body dancing, and all the dubious politics around it, that I wanted to explore. Who are these people dancing for? I can’t separate the funny Mr Bojangles dancing from the levity of the Huxtable family dancing. With the references to jazz and hip-hop, The Cosby Show credits seem like an attempt to reclaim ownership of the black body dancing.”

Butler has been working with the choreographer Jamila Johnson-Small to create a dance where she performs the dance moves of the entire cast. How did it feel to inhabit the body of Bill Cosby?

“Bill has this really strange way of moving, with this really low centre of gravity,” she adds. “And in most of the credits, there’s this final shot where he turns to the camera and there’s a close-up of his face.” Butler does the move to me, across our table, freezing in a to-camera pose before grimacing and dropping her head into her hands. “That close-up used to be so benign,” she says. “Now it’s a mugshot.”

Butler pulls out specific moments from The Cosby Show to discuss her own experiences. Total blackouts in the theatre will explore the subject of ԁrսɡѕ and date rape, while she uses hair to open up a discussion of race. “There were a couple of hair controversies in The Cosby Show,” she explains. “Someone who played Theo’s best friend ended up disappearing, apparently because he wanted to wear dreadlocks. Bill Cosby wasn’t into that. There was this need to present a clean-cut image – which brings up the question of what ‘clean-cut’ means.

“I’ve had some quite vocal criticism about wearing an afro. People come up to me and say: ‘Don’t you have any self-respect? How can you leave the house like that?’ This assumption that I’m gross or dirty, that I don’t care how I’m representing black people – even that I grew up without a mother, so nobody ever taught me how to do my hair properly.”

If you’re going to make a show about the Cosby allegations, you have to work out your opinion on the Cosby allegations. Or at least be willing to discuss them. And Butler is ready. “The show isn’t a biography or an indictment,” she explains. “I’m looking at the structural issues, what it says about authority and power – why some people are instantly believed, and why we have a fierce desire to defend their interests.”

She isn’t interested in defending Cosby. “I do think the stories are too compelling; that Bill Cosby hasn’t even come out and said: ‘I didn’t do this,’” says Butler, choosing her words carefully. “The subtext always seems to be: ‘But I was a celebrity – I was entitled. You were allowed to.’ But in a very basic way, I think we need to believe women – and that the effort put in to keeping these stories buried speaks to some degree of guilt.”

In the end, says Butler, she’s not dancing about Cosby to defend or attack the man himself. She’s not dancing to make a statement on behalf of all young, black, female artists. She’s dancing to ask questions, to interrogate our ideas about nostalgia, power, gender, blame and race. And she’s dancing – there, live, now – so she can bring into the present moment something that for too long has been dismissed as historical.

“The way the Cosby allegations are coming out of the 60s, 70s, 80s and the 90s – at what point can we stop seeing the past as an alibi to offset our own guilt?” she says. “We need to step up and stop using the past as an excuse.”